Sprawl, as defined in the classic Les Murray poem, is ‘the quality of the man who cut down his Rolls-Royce / into a farm utility truck’. Sprawl is also ‘doing your farming by aeroplane’ or ‘driving a hitchhiker that extra hundred miles home’.

Murray says he learned the term from his father who used it to describe ‘a kind of shirtsleeve nobility of gesture. Not pinched-arse Puritan at all’. Rather sprawl is ‘loose-limbed in its mind’. It assumes an easy surplus – ‘the fifteenth to twenty-first / lines in a sonnet’ – and runs no tabs. Never ostentatious it has no truck with ‘lighting cigars with ten-dollar notes’ or ‘running shoes worn / with mink and a nose ring’.

Sprawl, broadly speaking, is rural largesse: ‘an image of my country’, he says, ‘and would that it were more so’.

‘The Quality of Sprawl’ moonlights as a praise poem to rural Australia’s yawning landscapes and its inhabitants with a genius for making do. But its real job is to throw shade at the urban elite who, mentally cramped from years of vertical living, would see sprawl expelled from the Earth. Sprawl grins with ‘one boot up on the rail / of possibility’ and thinks that unlikely.

But Murray – a self-taught polyglot who famously plays at subhuman redneck – is not so sure. Sprawl is antithetical to political correctness, and Murray has the battle scars to prove it. The poem ends: ‘People have been shot for sprawl.’

◆

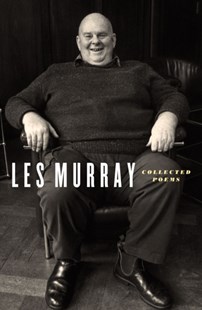

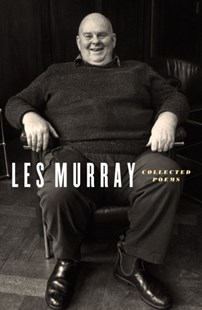

Les Murray was born in the small town of Naiac – north west of Forster and south of Taree – on 17 October 1938. The dropping of his latest Collected Poems – a handsome and weighty hardback bearing Murray’s trademark visage on the cover – is timed to commemorate the eightieth birthday of Australia’s most famous living poet.

I say ‘latest’ because, in good sprawl spirit, Murray’s been rolling out stockpiles of ‘all the poems he wants to preserve’ since 1991. Nevertheless Les Murray: Collected Poems soars above earlier remits. In compiling 15 books across a remarkable 50-year span – four from this century and 11 from the last –.it is his closest approximation yet to a lifetime of poetry.

But Collected Poems is more a sprawling selected – and, yes, he’s had six of those – than a genuine collected. Rather than reproducing each book as it appeared in print, Murray takes the axe most brutally to his early books but hacks small holes in the later ones as well.

Sometimes it’s not clear why a particular poem has been disowned – ‘Self and Dream Self’ from Waiting for the Past seems to me, as it must have to the editors at Poetry magazine who first published it, a perfectly good poem.

Other exclusions, under scrutiny, are forgivable and, in the rare instance, commendable: ‘The Abortion Scene’; or ‘The Massacre’, which empathises with the gunmen not the victims of an American high-school shooting. Both poems, however, survive online.

The irony of choosing the book as his preferred technology for the preservation of his poems is likely lost on Murray. In ‘The Privacy of Typewriters’ he describes himself as ‘an old book / troglodyte’ who ‘composes on paper’ and ‘types up the result’ on a typewriter – or he did, at least until it became impossible to buy new typewriter ribbons. Computers scare him, he says in the poem, not just for their ‘crashes and codes’ and ‘text that looks pre-published’ but also for that one ‘baleful misstruck key’ that could land him on a child pornography site and soon after in handcuffs.

Yet Murray’s digital presence is large. The Australian Poetry Library houses all the poems from his books up to 2006, and his eponymous website, run by enthusiast Jason Clapham, archives for posterity the very poems Murray claims to disown. Given Murray’s site gets more unique visitors in a month than he might expect readers for an entire print run, books seem headed the way of typewriter ribbons.

As a physical object Collected Poems is a colossal and immensely readable corpus that shows us what Murray sees looking back from eighty on a life built out of ink and paper. He has been thinking about his body of work, and constructions of his textual body, for a long time. As far back as ‘Evening Alone at Bunyah’ he told his father, ‘I only dance / on bits of paper’.

In his 1997 essay ‘Poemes and the Mystery of Embodiment’, Murray tenders an idea that ‘everything we make, especially if it is with passion, is a new body for ourselves’. He discloses the secret to canonical longevity:

‘We create our body of work, our corpus operarum, a very ancient metaphor, and we try to load every rift with awe, since that is the only fuel which can power its journey into future time’.

◆

Murray’s first book of poetry, The Ilex Tree, appeared in 1965 as a joint publication with Geoffrey Lehmann. A mere eight of Murray’s 25-poem contribution find refuge in the Collected, but those that do are as potent as anything he’s written since. The early poems are more measured than the later ones, but the eye for spectacle and genius for weird metaphor are unmistakably Murray.

‘The Burning Truck’ launches the Murray oeuvre with a shattering of crockery as fighter planes, coming in from the sea, set a town on fire. A ghostly truck – its ‘canopy-frame a cage / torn by gorillas of flame’ – is hurled driverless through the town, growing enormous, then disappearing out of the world.

Although Murray discards more than half the contents of his first sole-authored collection, The Weatherboard Cathedral introduced his most famous poem: ‘An Absolutely Ordinary Rainbow’. Atypically, it’s set in a city: ‘There’s a fellow crying in Martin Place’, the poem announces, ‘They can’t stop him’. The man gives full expression to his sorrow – ‘hard as the earth, sheer, present as the sea’ – then mops ‘his face with the dignity of one / man who has wept’ and hurries down Pitt Street.

Murray would go on to publish an average of three books a decade until the end of the century, each yielding handfuls of great poems that catapulted Murray’s name into Laureate circles. Among them: ‘Walking to the Cattle Place’ from Poems Against Economics (1972); ‘The Broadbean Sermon’ from Lunch and Counter Lunch (1974); ‘The Buladelah-Taree Holiday Song Cycle’ from Ethnic Radio (1977); ‘Equanimity’ from The People’s Other World (1983); ‘The Dream of Wearing Shorts Forever’ from The Daylight Moon (1987); the eponymous poem from Dog Fox Field (1990); and the ‘Presence’ suite from Translations from the Natural World.

But Murray’s millennial collection, Subhuman Redneck Poems – which earned him the TS Eliot Prize for Poetry and reprimands from his old foe, the urban elite – remains the standout. Long before Hilary uttered her career-ending phrase, Murray knew he’d been consigned to the Basket of Deplorables: he’s been trying to write his way out of it for the last half century.

Rereading these poems now, as they retreat deeper into history, a certain prescience can be glimpsed. Long before the Treasurer caved to cries for a Royal Commission, Murray was railing against the banks. ‘The Rollover’ inverts the social hierarchy to put bankers at the mercy of farmers: ‘Some of us primary producers, us farmers and authors’, it begins, ‘are going round to watch them evict a banker’.

‘Who buys the Legend of the Bank anymore?’ the farmer asks. ‘It’s all an Owned Boys story’. It ends: ‘No land rights for bankers.’

Similarly Murray’s poems took seriously the trauma of childhood bullying long before it was dinner-table conversation. Early critics found his reports of bullying inadequate to the scale of his resultant depression, but readers on closer terms with rejection were more sympathetic. ‘Burning Want’ – which today might serve as a key text for the incel movement – describes Murray’s sexual shaming at the hands of high-school girls as ‘erocide’ – the destruction of his sexual morale – which produced in him, he says, ‘a buried fury of sex and a terror of women’.

Murray’s four books of this century – Poems the Size of Photographs (2002), Biplane Houses (2006), Taller When Prone (2010) and Waiting for History (2015) – continue his display of linguistic dexterity but work to a smaller canvas. Herein his poetic impulse angles away from public argument toward an ethnographic project to memorialise the vanishing objects of his rural childhood.

Murray has a long history of diagnosing illnesses in poems: his depression, his son’s Autism and his own, the virulent liver infection that left him in a three-week coma in 1996. As he approached his eighth decade, hospital visits, nursing homes, and his own physical frailty arrived as new subjects for poems.

Waiting for the Past opened a new era of vulnerability: in ‘Diabetica’ a man ‘yawns upright / trying not to dot the floor / with little advance pees’; while in ‘Vertigo’ a man falls in a hotel bathroom and finds his ‘head in the wardrobe’. As stumbles increase in frequency – any time after sixty or before – it’s ‘time to call the purveyor / of steel pipe and indoor railings’, he says. The poem gestures toward a twilight that awaits us all:

Later comes the sunny day when

street detail gets whitened to mauve

and people hurry you, or wait, quiet.

◆

In ‘The Last Hellos’, Murray recalls his father’s final year: ‘Don’t die, Dad’ – the refrain goes – ‘but they do’. It ends with a son wishing his father God. My closing echoes the final stanza and repurposes it as a commendation: Snobs mind us off Murray / nowadays, if they can. / Fuck thém, I wish you Murray.

–

This article was first published in The Australian as ‘Les Murray’s Collected Is Really a Sprawling Selected‘ (17-18 Nov 2018)