The Mary Gilmore Prize is for a first book of poetry. This year there were 39 entries: 33 of them were authored by women. The short list of five, perhaps not surprisingly given the odds, is made up entirely of women: Emily Ballou for The Darwin Poems (UWA 2009), Helen Hagemann for Evangelyne and Other Poems (APC 2009), Sarah Holland-Batt for Aria (UQP 2008), Emma Jones for The Striped World (Faber & Faber 2009), and Joanna Preston for The Summer King (Otago UP 2009).

The Mary Gilmore Prize is for a first book of poetry. This year there were 39 entries: 33 of them were authored by women. The short list of five, perhaps not surprisingly given the odds, is made up entirely of women: Emily Ballou for The Darwin Poems (UWA 2009), Helen Hagemann for Evangelyne and Other Poems (APC 2009), Sarah Holland-Batt for Aria (UQP 2008), Emma Jones for The Striped World (Faber & Faber 2009), and Joanna Preston for The Summer King (Otago UP 2009).

At the time of writing, the winner of the Mary Gilmore Prize has not yet been announced; however, several of these titles have already won national (and, in Jones’s case, international) prizes, in some cases in competition against highly esteemed and established poets. Unfortunately, these particular books were published just prior to the catchment for this review so I was not afforded the pleasure of reviewing them here. But I bring up the Gilmore shortlist in any case because I think it best illustrates a point that poetry critics and reviewers have been making for some time now: the most exciting poetry in Australia seems to be found, very often, in first books by young female poets.

The emphasis on female authors, it’s worth adding, has become evident not just in poetry publishing in Australia but also overseas and in other genres. In 2009 all eyes were on the women who swept the heavyweight international literary awards: the Nobel Prize in Literature went to German author Herta Müller who, the Swedish judges said, “with the concentration of poetry and the frankness of prose, depicts the landscape of the dispossessed”; the Man Booker went to Hilary Mantel for her novel Wolf Hall; the International Man Booker went to Alice Murno for Too Much Happiness; and Elizabeth Strout won a Pulitzer for her short story collection, Olive Kitteridge. Is it an accident they were all women; stacked judging panels; a mini-trend? Or are the tides turning?

Back home in Australia, similar questions were being posed in poetry circles. Reviews that commented on the predominance of young female talent among poets left some of the authors in question feeling not so much flattered as wondering – in conversation and in blogs – why they were being singled out as female: they preferred, some of them said, to be judged – and categorised if they must be categorised – based on some quality of their writing, not on the particular pairing of their chromosomes. It’s not that it isn’t interesting to think about the poet’s sex (and for that matter his or her gender and sexuality), they argued, but only if such interrogations yield interesting results pertinent to their work. Many of the same poets deemed that this clumping, as they saw it, did not. As might be expected, however, some bloggers (some of whom were poets, some critics) accused them of being overly sensitive: the “young female poets” were being complimented, not being thrown into a now non-existent gender ghetto. Then one anonymous blogger – a male? – smirked: “I’ve heard them referred to as the Ladies of the Lyric”. The condescension was as loud as the phrase is alliterative, and the sexist cat – to stretch the ghetto metaphor – was out of the bag and running down an alley.

This review is not the appropriate forum for interrogating lyricism, nor its alleged linkage to female poets. There are too many books that need attention to waste space theorising. But some of these observations – and objections – were foremost in my mind as I surveyed a year’s worth of poetry books sent to me for review. Having read the books on offer, and thought about them, I feel safe to dismiss the gender question as not particularly pertinent this year. And I would dismiss it immediately if it weren’t for the presence of a very striking book in this catchment that happens to be yet another first (full length) book by an Australian female poet: Ghostly Subjects (Salt 2009) by Maria Takolander. It’s also one of the darkest books on offer.

Takolander’s poems are ruinous, diabolical, all the more so for their polish and precision. Here, as in Baudelaire, beauty is inextricably linked with evil: it’s “the dark italics”, as Wallace Stevens phrased it, that compels the poetic imagination in these poems. Not surprisingly, it’s often night-time in a Takolander poem: night is “the dangerous time”, the speaker says in “Drunk”, adding “anything goes when the light goes.” In “Pillowtalk”, a devastating poem in which innuendo lingers like poison, “There is no rest. / Nights are for unreason.” It opens with a stunningly precise if ominous image:

Inside the bedside drawer,

The knife blade empties

Like an unwatched mirror

At night.

The child-speaker’s psychological “bed was made” by whatever happened to her during those long, black hours. We’re not told exactly what did happen – some words should never see the flood of day – though the father’s rifle leaning behind two old coats does lend itself to a Freudian interpretation. The poem closes with the speaker’s troubling confession that she hides bullets in her mouth – her invocation as a poet? – and grinds them down like candy. Almost all the poems in Ghostly Subjects are similarly menacing, but they’re also stylish and very smart. Don’t be surprised if they take up residence in your body after reading them, like “a tree full of vultures … / hulking like souls” (“Tableaux”) – it’s just that kind of book.

This year’s catchment, in contrast to the previous year, contained few first-time authors but instead saw a number of fine books by Australia’s senior poets. In Les Murray’s Taller When Prone (Black Inc 2010) the poems, as seen in his last few books, are shorter than in his early work, and so is his line. His thinking seems tidier than before, the breathing more relaxed, but this new collection nevertheless showcases Murray’s trademark sally and satire, along with the whimsicality and wisecracking wordplay that safeguards his rank as one of the best poets writing in English. The title of the collection comes from the poem “The Conversations”: “A full moon always rises at sunset / and a person is taller when prone”. As depicted on the cover, these seemingly paradoxical lines are resolved in the image of a man’s late-day shadow stretching into a paper-thin giant. But as often is the case with Murray it is also a pean to the imagination, the idea that a person is more than himself when asleep and dreaming: “a person is taller at night”, the speaker also asserts. Or it might also connote that a person reaches full stature only through the canonising processes afforded by death.

It struck me reading this book that it is haunted not only by Murray’s old foe, the black dog of melancholy, but also by the spectre of insanity. Like Lear – “O! let me not be mad,” cries the king – the speakers in Murray’s poem fear losing their mind. In fact King Lear is evoked in one of the most striking poems in the collection, “King Lear Had Alzheimer’s” – a poem that draws parallels between Cordelia’s disinheritance and, to read intertextually, that of his own father’s. The poem pushes a bleak, almost Hardyesque idea of fate and what it does to a human:

The great feral novel

every human is in

is ruthless.

Alzheimer’s appears again in the poem, “Nursing Home”. “Don’t outlive yourself”, it warns as the speaker recounts the losses and indignities of old age: “the end of gender / never a happy ender”. Then, proving he still can dance on bits of paper, Murray conjures “a lady” in a nursing home who has “who has distilled to love / beyond the fall of memory”:

She sits holding hands

with an ancient woman

who calls her brother and George

as bees summarise the garden.

“Summerise” is quintessential Murray. Sonorous, yes, but it’s also a pun on the season – “summer-ise” – at the same time granting bees the busy work of joining the dots in this bittersweet scene.

Bees bring to mind Dorothy Porter and her seventh and final collection of poetry, The Bee Hut (Black Inc 2009). Written in the last five years of her life, it was completed just before her death in December 2008. “The bee hut became a metaphor for these last years of [Porter’s] life”, Andrea Goldsmith writes in the Foreword: “she marvelled at the bees, as she had always marvelled at life, but she was also aware of the danger amid the sweetness and beauty”. In the titular poem, the speaker tells of a swarm of bees that has taken over an old shed:

I love the bee hut

on my friend Robert’s farm.

I love the invisible mystery

of its delicious industry.

But do I love the lesson

of my thralldom

to the sweet dark things

that can do me harm?

Even Porter’s love cannot forego awareness of the forces that hurt and destroy, even if she would have them subsumed within a celebratory synthesis. Like the Romantics who feature in a number of Porter’s poems – Keats, Byron – Porter is often at her finest when voicing contradictory surmises about the relationship between the imagination and the pressures of reality. As Keats did in “When I Have Fears”, Porter stared down her own death in her final poems. But unlike Keats, Porter stays wildly passionate – “exorbitantly flamboyant”, even, like the art deco buildings she sees through her window at the Mercy Private Hospital in Melbourne – until the end. Her last poem, “View from 417”, was written two weeks before she died. It’s impossible not to love the stubborn optimism of the collection’s last words:

something in me

despite everything

can’t believe my luck

In an earlier poem, “Early Morning at the Mercy”, the speaker, at 6 a.m. in the “cool-blue cool / of early morning”, lets her tea go cold and turns her mind to Gwen Harwood’s Bone Scan poems. “How on earth she could write / so eloquently in hospital”, she wonders. The Bee Hut – poignant, powerful, spirited – has me asking the same question of Porter.

Speaking of luck, Catherine Bateson takes up the theme and spins it on her head in her poem “The Day Complains” from Marriage for Beginners (John Leonard Press 2009). Feeling distinctly unlucky – the speaker in the humorous if unlikely guise of “a day” – shows, as do many of Bateson’s poems, that poetry and comedy are good bedfellows. It begins:

Why can’t you take me as I am

the way I have to take you –

hungover and foul-mouthed

in your Cookie Monster pjs

last night’s argument with the ex

banging away in your head

“The Day” continues its admonishment of the poet-addressee and concludes with a king hit Dorothy Porter, for one, would love:

So roll over, close your eyes

and sleep me off.

I’ll go down to the nursing home

where they’re grateful just to see me.

Some say Tom Shapcott’s Parts of Us (UQP 2010), his fifteenth book of poems, is his best yet. An unflinching meditation on death, aging, and the unheralded losses that come with physical decline, it is at times painfully candid. In the sonnet “Miranda at Two”, just as the speaker’s young granddaughter is “tumbling toward speech” – learning that “sound is the conduit for all those urgent things inside” – the speaker finds that his own capacity for language, or more accurately his capacity to sound language, is closing down around him:

my own tongue thickens and the muscles distort

language so that I hesitate to express myself and cannot

control articulation. Silence rather than speech

is my new mode.

The final couplet has Miranda laughing up at the silent poet and adopting as her own the poet’s task of naming; she addresses him – though we’re not told by what name – “with perfect symmetry”. Despite the isolating effect that the loss of speech has on a human life – which is of course the heart of this poem – it is difficult to discern self pity in these lines. Speech is to a poet what hearing is to a musician, and one imagines the loss should be more terrible than it is presented in this poem. But as a poet he is still able to write – and this he does exceptionally well – but more than this he can listen.

Hearing is a sense Shapcott revels in. Everywhere his love of classical music is evident, particularly in the first section of the book where poems about Stravinsky, Vivaldi, Schoenberg and other musicians abound. But in a startlingly beautiful and enigmatic poem called “Nocturne” it’s not humans who make music, but the “night’s full choir / of possibilities”.

Listen. The night is dark

though it’s amazing how much light

pretends otherwise – the stars

could be hidden by clouds but this

street and advertisement message

hoodwinks us into believing

our fate is otherwise.

We are alone.

The poet says he knows “the ultimate of silence” but still, he says, he “cannot believe silence / will truly happen to [him]”. Parts of Us tells us it won’t.

With Judith Beveridge’s unquestioned reputation as one of Australia’s most highly regarded poets, even knowing her work well it comes as a shock that Storm and Honey (Giramondo 2009) is only her fourth collection of poems. But those who know poetry know that quality and quantity are not necessary apportioned in equal measure, as Elizabeth Bishop with her small handful of exquisite books illustrated so well. As Bishop sometimes did, Beveridge takes the ocean as her subject and makes it her element. Storm and Honey opens with a boy, or what was left with him, being pulled from the steaming gut of a shark, and it ends with a shark in “The Aquarium” that the speaker cannot forget:

how its eyes keep staring, colder than time – how it never

stops swimming,

how it never closes its mouth.

The shark, the ultimate predator whose open mouth causes “our hearts [to] burn inside us”, becomes a symbol of unceasing hunger, the cause of so much grief. It’s this philosophical dimension of Beveridge’s poems that gives them resonance beyond her capacity to carve an intricate image or to craft into language the sounds of the nature and the rhythms of work. Though it must be said that she does the latter exceedingly well.

Like Porter, Beveridge also has a poem about a bee hive – hers is in bushland, “in an old toppled red gum”:

Sometimes, I’ll picture that old fallen

red gum exhaling bees from the shaft of its cracked

trunk. I’ll picture my hand deep in the gum’s

center, warm with the running honey; the swarm

suddenly around my head like a toxic bloom,

and the noise, the noise in my ears – still wuthering.

These remain among the most intoxicating lines I have read in a long while. As with Murray’s “summarising” bees, Beveridge’s wuthering bees are evidence of her power as a poet to breathe life into forgotten words and show how their presence in our lexicon is earned, not as a luxury but as a necessity that we may live life fully.

Similarly intoxicating, Sarah Day’s Grass Notes (Brandl & Schlesinger 2009) is, to adapt a phrase from her poem “Fungi”, a “beacon of freakish beauty”. The rapturous poem “Apples” opens with a couplet as majestic as any – “these apples have weathered / the rise and fall of civilisations” – and traces their cultural trajectory along the Silk Route to ancient Persia , branching into varieties “illustrous as any dynasty”, passing through art and religion and science to end again as themselves: “These half dozen apples on a plate – / currency of Everyman’s pleasure.

But not all her poems ride such heady top notes: Day is also a master of gravity. As seen in the quiet devastation of “Wombat” in which the speaker attempts to haul the bulk of a dead wombat – his head “big as a person’s”, his “grey palms big and soft as / a child’s” – off the road.

In the end, the only way to move his bulk

was to hook an arm under each of historical

and haul him like a dead man

off the yellow gravel across the ditch

and leave him on the grass bank

as if in deep repose.

The speaker projects the wombat’s slow decay as his body collapses from within and “recedes into two dimensions”:

An arrangement of bones upon the drying grass,

summer warming up his patch of earth;

the forest ravens jawing higher up the hill,

a magpie carolling each lightening morning

and skylarks overhead

rising on each ascending note.

It’s this kind of movement that gives, along with her many other staggeringly good poems, evidence for the claim on the back of the book”: Day is indeed one of the most considerable of modern Australian poets.

Ascending notes bring to mind Alan Gould’s twelfth book of poems: Folk Tunes (Salt 2009). The collection, filled with rhymes and rhythms that accord with its title, is filled with light: sometimes it glances off the beloved’s “head of silver curls” (“She Sings Him”); other times it glints from a juggler’s cleaver (“The Juggler and My Mother”). Music abounds but it’s when the darkness of satire enters the minds of these otherwise romping and playful poems that things turn operatic. As in the brilliant but biting “In Thought They Lived Like Russians”, which begins:

They stripped the furniture from their flat,

and put on gloves to pay the rent,

they scorned their freeholds in the fat

of middle class content.

The poem concludes, like a Russian novel, with a reconciling of opposing emotions, underscored by a dazzling enjambment that spins meaning on its head:

They were the fate within the novel

where joy and disenchantment join

at some not altogether sane

not altogether pain-

ful level.

Likewise Ross Bolleter celebrates, mourns, and charms in equal measures in Piano Hill (Fremantle Press 2009). Bolleter – a musician who runs tours at a ruined piano sanctuary in WA – possesses the whimsical ear of a composer, paired (not pared) with a mind ruthless as a zen scalpel. “Suite for Ruined Piano” is a knockout sequence that, as a whole, is an unapologetic ode to the piano. There’s a little bit of jazz in the dazzling “Everytime We Say Goodbye” – but it’s mostly about a Sudanese poet who, after sharing with the speaker a meal of “chili mutton rice and onion”, recites a poem in Arabic (translated by an English woman). But it’s what the Sudanese poet doesn’t say that gives the poem its crushing ending:

‘Memory’, says the poet, trying not to recall

waking with a gun in his face, soldiers

ripping the coverlets off his children –

who burrowed into their beds abandoning

their bodies like the remains of a feast

not worth touching.

Africa looms large in Marcelle Freiman’s White Lines (Vertical) (Hybrid 2010). “Mercy” is a powerful and moving portrait of a nurse in Johannesburg who each night “comes from Soweto / to the white suburbs” to look after the speaker’s father. The end is amazing:

When he died she walked

into our house with its candles,

her hips arthritic, bent with stroke, still massive:

round the family table, she held our hands, opened her Bible

closed her eyes, and sang,

her voice like a bell –

you could feel God at her shoulder,

waiting over the horizon.

While some poets stare into darkness for inspiration, Andrew Taylor looks into the light. The Unhaunting (Salt 2009) is Taylor’s fifteenth book of poems – his first since confronting a severe illness in 2003 – is brilliant. The collection takes as its title, and overarching theme, the idea that ghosts are real and live among us – not as spirits but as fellow humans, whose torment is our haunting. Death is their – and our – only release.

Taylor plays with the idea in “The Carillon Clock”, a gorgeous poem in which time haunts literally and figuratively. It describes an old pendulum clock that came from France, “possibly in the time / of the Second Empire” but which “neither trilled nor peeled / … rather it breathed”. One night the speaker in his insomnia – “already awake” – hears the clock “in barely audible words” offer up its final wisdom before settling into silence forever:

And to you –

my lonely listener – I say, try to live

beyond time, in that dimension

no one can measure. Then the voice fell silent

and for many years the clock stayed

hanging on the wall. Probably

its outline is still there on the plaster.

You can feel, in this collection, Taylor getting closer and closer to the things he wants to say in his vocation as a poet. In “The Impossible Poem”, the final poem that serves as a coda of sorts for the collection, the poet – or “lonely listener” – conjectures:

There are only two poems –

the one you write

and the one always undoing

your words

As you get older, he continues, the latter, that impossible poem, “stretches its fingers toward you” and you can maybe, just, feel what that poem might actually be:

as Adam might have felt it

when God reached across the Sistine ceiling

toward his touch.

In this impossible poem, all things – a warm stone, a stranger’s smile – become a word or a phrase, a kind of living language we can learn to appreciate even when we can’t quite fully comprehend it.

♦

In Gillian Telford’s Moments of Perfect Poise (Ginninderra Press 2008) the poem “Hunted” is a standout. Taking up an activity dear to the heart of Dorothy Porter – driving fast, that is – the speaker is “alone / late at night” with a pack of of cars close behind and “coming closer”: and that’s when you know, the poems ends shifting gears into metaphor, “how it is / for a gazelle / losing ground”. There’s a sense of urgency, too, in Susan Hawthorne’s Earth’s Breath (Spinifex 2009), which takes cyclones – local and mythical – as its subject. Perhaps one of the most haunting poems in the collection is “Storm Birds”, which opens with the image of storm birds at rest, looking like “a boat stranded in a tree / in flight a crucifix”. In part two of this poem:

Curlews are calling

presaging wind wail out of stillness.

Silent for weeks

their cry is an agony

the keening wind of dispossessed souls.

With Birds in Mind (Wombat 2009), Andrew Landsdown joins Judith Wright and Robert Adamson, among others, in dedicating a whole book largely to poetic birds. But it’s as much a book about the imagination and memory as it is about animals: “Now they’re gone I see them / again”, the speaker says in “Kangaroo Crossing” – “kangaroos bounding / through the troubled water // and a heron flying up”. Birds abound – cockatoos, corellas, pelicans – in unexpected water in Mark O’Connor’s Pilbara (John Leonard Press 2009). Meanwhile Vivienne Glance goes underwater in her collection of luscious and imagistic poems, The Softness of Water (Sunline 2009), as best seen in the end of “Desire”:

A golden fish

brushes her leg

slips into the folds

of her floating dress.

By contrast Nathan Shepherdson, enigmatic poet that he is, sometimes seems more concerned with unseeing than seeing in his second book, Apples with Human Skin (UQP 2009). Poems for Shepherdson are not images, nor are they answers, nor even questions: they are simply possibilities and alternatives. Like a zen koan, a Shepherdson poem can be pondered for months or it can be grasped in a flash – there’s no telling when it will release its ore. The idea, the axiom, the paradox is paramount in his work, as asserted in section “5” of “the easiest way to open the door is to turn the handle” – a long but straightforward title for a poem whose numerical sections run, quite naturally, backwards:

The idea of a wall

is defeated when the wall is built

tearing it down does not defeat the idea of tearing it down

♦

Perhaps the most handsome books in the catchment are the signed and limited-edition chapbooks produced by Whitmore Press. Barry Hill’s Four Lines East (Whitmore 2009) – rife with the “incessant vigor of thought” – is a small book intent on interrogating big realities. Hill is not afraid of abstractions – “no self no soul no being no life” – but he always drags them down to earth, as in the gorgeous poem “Noodles” that succeeds in shattering such concepts with its final image:

In a blue sweater, pants maroon

like Tibetan robes

the man stands with a golden net

hauling it up like noodles.

Also from Whitmore Press’s chapbook series, The Pallbearer’s Garden (2008) by A. Frances Johnson is, to use the words describing her Auntie’s garden, “caught by wind / and singed by fire” (“Floracide”). Each poem is a “repeatable beauty”, even when the poet is in the midst of grief and horror. The heavyhearted poem “Pallbearer” ends with unexpected levity: “I lift, helft and hold – shore up / howling lightness, lifting”. Then there’s Brendan Ryan’s Tight Circle (Whitmore 2008) which, though a compact chapbook, carries the weight of a full-length collection. The collection is named for a devastatingly good poem the centres on an uncle’s burial: the undertakers ask the family “made straggly with grief” and who “need distance from the hole” to form a tight circle around the grave. They “mutter / through the Lord’s Prayer” as the farmer-undertakers “lower [the] uncle into darkness”. The poem ends with a portrait of the speaker’s father (the dead man’s brother) that proves that life moves in concentric circles:

Burying has aged my father

softened his handshake.

He wakes in the night to exercise his new replacement knee.

Each afternoon he leans against the front fence

with his crutches talking to anybody who’ll stop;

he has to know what’s going on,

and when he’ll be allowed to drive out to the farm

to see the cows

bunched up in the yard

in a tight circle.

Sadly, there are two posthumous books – in addition to Dorothy Porter’s discussed earlier – in this year’s catchment: la, la, la (Five Islands 2009) by Tatjana Lukic and Beautiful Waste (Fremantle Press 2009) by David McComb of the post-punk band, The Triffids. Although she published four books of poems in her homeland, the former Yugoslavia, la, la, la is Lukic’s first collection of poems in English since she migrated to Australia in 1992. The title poem appears to be a conversation, perhaps by telephone, in which she assures a worried querent that, no, she was “not in the square when a grenade hit”; nor was she “forced from her home” nor taken to “the camp”. But she did see “corpses floating along the river” and “someone changed the locks and lay in [her] bed”. “Yes”, she admits, she “remembers everything” but, like survivors who want to survive must, she tucks the memories in a place in her mind where the trauma cannot hurt her:

the whole day

what did I sing?

about a cloud and a bird

a wish and a star,

la la la,

yes, nothing else

The speaker’s levity may not convince, but the psychological realism is chilling. Lukic writes of her war-torn homeland with such directness that even when she turns her attention to her new life in the sleepy Canberra suburbs, the scarring – darkened by the contrast – still shines through. Lukic died of cancer in 2009.

Many of the poems in McComb’s book (written over the course of his short life) hold a fascination with mirrors: doubling is everywhere. It is as if speaker can’t quite hold himself together in a single psychology. In “You’re My Double” the speaker is scared to sleep by the mirror; in “You My Second Skin” the speaker wants to “peel you off me”; and a quatrain called “Nature’s Warning” has the poet driving through the mist of Northern England imagining his “belated and her substitute” for him, lying in “a double bed somewhere, kissing”. If you like Leonard Cohen’s music you’ll enjoy Beautiful Waste. The two lyricists share an aesthetic that embraces the ceremonies of suffering, finding great beauty in trauma and addiction, full release only in brokenness. In “Ode to January 1989”, McComb writes that “everything sins, suffers, grows”.

Which brings to mind the closing lines of the first poem in Chris Mansell’s sixth book, Letters (Kardoorair 2009), which puts the reader by the Mediterranean Sea, drinking “thick, sweet coffee” and thinking of those “who have gone before”. Then the poem would have you “visit Cavafy’s house / and think”:

why poetry is filled to the heart

with humanity and this grief

shall be long and strong

and you will weep

one more time and the world

will be laughably fresh

as it has been

this old world

all along.

♦

Originally published in Westerly 55.1 (July 2010): 21–38.

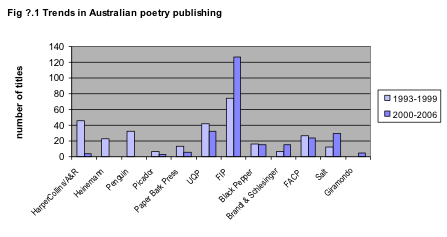

Once asked what poets can do for Australia, A.D. Hope replied: “They can justify its existence.” Such has been the charge of Australian poets, from Hope himself to Kenneth Slessor, Judith Wright to Les Murray, Anthony Lawrence to Judith Beveridge: to articulate the Australian experience so that it might live in the imagination of its people. While the presence and potency of the Australian landscape remains an abiding interest, a great deal of Australian poetry has been innovative and experimental, with poets such as Robert Adamson, Michael Dransfield, Vicki Viidikas, John Forbes, Gig Ryan, J.S. Harry, and Jennifer Maiden leading the way. The richness, strength, and vitality of Australian poetry is marked by a prodigious diversity that makes it as exhilarating to survey as it is challenging to encapsulate.

Once asked what poets can do for Australia, A.D. Hope replied: “They can justify its existence.” Such has been the charge of Australian poets, from Hope himself to Kenneth Slessor, Judith Wright to Les Murray, Anthony Lawrence to Judith Beveridge: to articulate the Australian experience so that it might live in the imagination of its people. While the presence and potency of the Australian landscape remains an abiding interest, a great deal of Australian poetry has been innovative and experimental, with poets such as Robert Adamson, Michael Dransfield, Vicki Viidikas, John Forbes, Gig Ryan, J.S. Harry, and Jennifer Maiden leading the way. The richness, strength, and vitality of Australian poetry is marked by a prodigious diversity that makes it as exhilarating to survey as it is challenging to encapsulate.