The 1990s heralded a new ethos in Australian book publishing: poetry was no longer presumed to be a prestigious staple on the list of a serious publishing house. With mergers and takeovers happening left and right in the commercial publishing sector, poetry for all its ‘cultural worth’ was told to pay its way in dollars or be gone. But with characteristically small print runs and booksellers hesitant to stock specialty books this was a big ask. By the decade’s end, Angus & Robertson, Heinemann, Penguin and Picador had abandoned poetry almost entirely, leaving a slew of canonical Australian poets – including Kenneth Slessor, Judith Wright, Les Murray and many others – without a publisher.[1] Of course it was part of a larger trend: in 1999 Oxford University Press also terminated its poetry list and dropped expatriate-Australian poet Peter Porter, along with his British colleagues. For a brief moment, verse novels caused a flurry of excitement but this soon settled into fad. Dorothy Porter’s Monkey’s Mask (Hyland House, 1994) and Murray’s Fredy Neptune (Duffy & Snellgrove, 1998) seemed hopeful crossovers into relatively larger fiction markets.[2] A few years later Alan Wearne’s The Lovemakers, Book One (Penguin, 2001) won the NSW Premier’s Kenneth Slessor Prize for Poetry (as well as Book of the Year) and the Arts Queensland Judith Wright Calanthe Award, but this didn’t stop Penguin from pulping their unsold stock and declining publication of the completed second volume. During this time only the University of Queensland (UQP), as David McCooey points out, remained a significant publisher of poetry.[3]

The 1990s heralded a new ethos in Australian book publishing: poetry was no longer presumed to be a prestigious staple on the list of a serious publishing house. With mergers and takeovers happening left and right in the commercial publishing sector, poetry for all its ‘cultural worth’ was told to pay its way in dollars or be gone. But with characteristically small print runs and booksellers hesitant to stock specialty books this was a big ask. By the decade’s end, Angus & Robertson, Heinemann, Penguin and Picador had abandoned poetry almost entirely, leaving a slew of canonical Australian poets – including Kenneth Slessor, Judith Wright, Les Murray and many others – without a publisher.[1] Of course it was part of a larger trend: in 1999 Oxford University Press also terminated its poetry list and dropped expatriate-Australian poet Peter Porter, along with his British colleagues. For a brief moment, verse novels caused a flurry of excitement but this soon settled into fad. Dorothy Porter’s Monkey’s Mask (Hyland House, 1994) and Murray’s Fredy Neptune (Duffy & Snellgrove, 1998) seemed hopeful crossovers into relatively larger fiction markets.[2] A few years later Alan Wearne’s The Lovemakers, Book One (Penguin, 2001) won the NSW Premier’s Kenneth Slessor Prize for Poetry (as well as Book of the Year) and the Arts Queensland Judith Wright Calanthe Award, but this didn’t stop Penguin from pulping their unsold stock and declining publication of the completed second volume. During this time only the University of Queensland (UQP), as David McCooey points out, remained a significant publisher of poetry.[3]

Since its first poetry title in 1968, UQP has published at one stage or another just about all of Australia’s important contemporary poets, including David Malouf, John Tranter, Judith Beveridge and Anthony Lawrence. Its impressive backlist, relatively large infrastructure, and its access to national distribution meant that competition was tight for its annual two or three poetry titles (which was intermittently topped up with books, such as Sam Wagan Watson’s award-winning Smoke Encrypted Whispers from the Black Australian Writing list, or Jennifer Strauss’s The Collected Verse of Mary Gilmore 1887–1929 from the Academy Editions of Australian Literature and published by UQP in association with the Australian Academy of the Humanities). [4] In 2002, pre-figuring a review of operations, the Press decided to outsource its poetry editorship in order to trim overheads on poetry titles, which with few exceptions – Peter Skrzynecki’s wildly successful Immigrant Chronicle among them – required financial buoying from income-generating fiction titles. To the resounding relief of poets around the country, following a 2005 restructure the Press formally announced a renewed commitment to poetry and increased its list to five or six poetry titles per year. The new list included the annual Arts Queensland Thomas Shapcott Poetry Prize for a manuscript from an emerging Queensland poet – which despite its regional catchment enjoyed national success with award-winning titles by Lidija Cvetkovic and Jaya Savige; a selected or collected volume of poems by a senior Australian poet; and The Best Australian Poetry series established in 2003.

As publishing opportunities for poets grew increasingly rare Five Islands Press (FIP), founded by Ron Pretty in 1987, increased in prominence. As part of its Mainstream Program, FIP published about ten poetry titles per year, while its annual New Poets Program published 32-page chapbooks by six emerging poets. From time to time, the series was criticised for being too large to maintain a consistently high quality, nevertheless it launched the careers of a number of 1990s poets who went on to enjoy critical success – Peter Minter and MTC Cronin among them – in much the same way as Martin Duwell’s Gargoyle Poets series did for Australian poets in the 1970s. In 2002 FIP moved from the University of Wollongong to the University of Melbourne and was made integral to the newly established Poetry Australia Foundation.[5] In 2006, the Foundation scored a major coup when the Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) promised an initial sum of $140,800 to assist in establishing the Australian Poetry Centre in East St Kilda. Shortly thereafter, however, FIP announced on its website that Ron Pretty would pass the leadership of the imprint to Kevin Brophy and others in mid 2007, and that FIP would not only reduce its annual titles but also cease the New Poets Series for the foreseeable future.

During this time there were also some newcomers. In 1999 John Kinsella, Clive Newman and Chris Hamilton-Emery formed a partnership to develop Salt Publishing. Salt, which then moved to the UK in 2002 and set up offices at Cambridge, put print-on-demand technology to good use to produce a significant list of attractive (if often difficult to find) books by Australian poets such as Pam Brown, Jill Jones, Kate Lilley, Peter Rose and many others. In the same year Ivor Indyk opened a new arm to his publishing house and began publishing poetry titles under the Giramondo book imprint, which got off to a fine start with prize-winning books by Emma Lew, Judith Beveridge and Jennifer Maiden. Other small but noteworthy presses include Brandl & Schlesinger and Black Pepper, as well as Vagabond, Picaro Press and PressPress which all specialise in chapbooks.[6] David Musgrave started Puncher & Wattmann in 2005 and Paul Hardacre’s papertiger media launched its Soi 3 Modern Poets imprint in 2006. Unfortunately there also were some departures from the ranks of independent publishing. Robert Adamson and Juno Geme’s Paperbark Press closed in 2002 after seventeen years of publishing some of Australia’s best poets; and Duffy & Snellgrove closed shop in 2004, leaving Murray once again without a publisher (fortunately Black Inc. was to inaugurate a poetry list with Murray’s Biplane Houses as its first title). Pandanus Books, based at the Australian National University, ended its poetry publishing days in 2006 with Windchimes: Asia in Australian Poetry, an anthology comprising poems that offer perspectives on Asia by eighty-six Australian poets.

As might be expected during these lean years, poetry anthologies increased in importance. In 1998, Thomas Shapcott edited his sixth poetry anthology, The Moment Made Marvellous, which was made up of poems by 70 UQP poets. Paperbark Press’s Calyx: 30 Contemporary Australian Poets anthology, edited by Michael Brennan and Peter Minter, came out in 2000 with a selection of poems by poets who first came to prominence in the 1990s. A year later Five Islands Press also came out with a ‘new poets’ anthology: New Music: An Anthology of Contemporary Australian Poetry edited by John Leonard. 2003 saw an embarrassment of poetry anthologies with UQP releasing the inaugural issue of its Best Australian Poetry series in September and Black Inc. releasing its inaugural Best Australian Poems a month later. Despite their similarity of titles, the anthologies came with different briefs. UQP’s anthology changes its guest editor annually, selects exactly forty poems that have been previously published in print journals and includes biographical information and author notes, whereas the Black Inc. anthology changes editors arbitrarily, includes more poems and poems from a variety of sources but does not include information about its contributors. Both publishers have reported healthy (by poetry standards) sales.

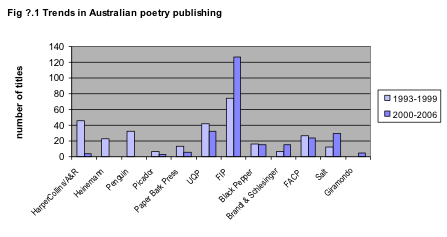

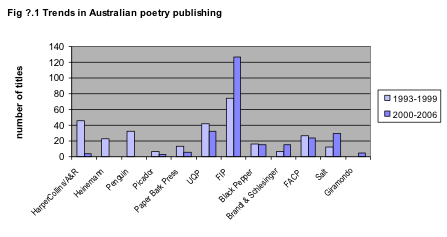

Many would expect that poetry book numbers would decline during this period of contraction and indeed they did. In the years between 1993 and 1999, over 250 books of poems were published in Australia each year; by 2006 this figure had been reduced by about 100 titles. Although comparable to figures from the 1970s – the decade lauded by many for fashioning a resurgence of poetry – a thirty-five per cent increase in the Australian population during the same interval summons sobriety. What’s more, the total number of poetry books published during this period makes the sector appear healthier than it might in fact be, in large part due to FIP’s New Poets Series which offered abundant publishing opportunities for emerging poets while the situation at large for developing and established poets remained impoverished. It is also important to note that the majority of poetry books are presently being published by small presses (including self-publishers) that often do not have sufficient access to resources, distribution and marketing to have their books noticed by readers. Under these conditions the thus-far unchallenged maxim that ‘poetry doesn’t sell’ becomes self-fulfilling prophesy.

Despite continued problems associated with distribution, marketing and sales, many poets and critics have observed that interest in poetry, oddly enough, is booming.[7] Poetry festivals have sprung up around the country – there’s even a National Poetry Week – poetry readings are held in cafés, pubs and libraries, and poetry ezines, blogs and discussion boards are burgeoning on the Internet. Writers’ centres and university creative writing programs around the country have been quick to respond to the increased demand for poetry workshops and classes. Poetry’s increased profile in high school curricula, particularly in New South Wales, has led not only to new generations of young readers interested in reading and writing poetry, but also to soaring sales for the poets lucky enough to be set on the compulsory reading lists. Poets in this enviable position – including Peter Skrzynecki, Bruce Dawe and John Tranter – can often compete on sales figures with fiction authors.[8] As an overall trend, poetry’s rising popularity is perhaps more noticeable in the US where a Billy Collins title can approach a print run of 100 000 copies; nevertheless poetry readership in Australia looks comparatively good when figures are adjusted for population. As Les Murray has pointed out, poetry in Australia enjoys a much larger readership in proportion to population than in most Western countries.[9] Whereas a typical US poetry title (Billy Collins aside) runs to about 1 500 copies, a poetry title by a reasonably well-known poet in Australia (at about one-fifteenth of the US population) runs to about half the US number. While these are only break-even figures – a ‘slim volume’ of poems costs about $5 000–7 000 in editorial, design and production costs – it is interesting to speculate as to what the figures might look like if Australian poetry titles were afforded the same publishing and marketing opportunities that other genres often enjoy. The extraordinary renewal of interest in Auden, for instance, after his poem appeared on screen in Four Weddings and a Funeral would seem to indicate that advertising works, even for poetry. But film options aside, the Australian market remains wide open to publishers who seek to make the most of the current poetry revival.

In the meantime, there are a number of things publishers can do raise the profile of their poetry titles. In addition to keeping a tight list of well-known and respected names that help carry titles by new poets, publishers can also avail themselves of state and federal publishing subsidies. While funding varies from state to state, the Literature Board of the Australia Council offers assistance to publishers with subsidies to support up to four poetry titles (including selected and collected editions) a year. The subsidy on offer for poetry is set at about half the rate for prose titles due to the assumption that it is less expensive to produce a book of poems than a book of prose (perhaps it is but it remains difficult to prove as poetry publishers have long survived by cutting corners). While the subsidy is helpful to poetry presses, it offers little incentive for publishers of mixed genres to put forth poetry titles over prose. Further complicating matters is the proviso that the titles must have a minimum print run and prove national distribution in order to qualify for funding – requirements that with the growth of print-on-demand technology have become increasingly difficult for small poetry publishers to fulfill as well as for the Board to monitor. Even so, the Council’s logo on the imprint pages of almost every Australian poetry title one encounters would seem to indicate that the initiative is keeping a good number of independent poetry publishers in business.

Many publishers like to see that individual poems have been published in literary journals prior to appearing in book format. This serves not only as a means of developing a readership for a poet’s work, but it also verifies that the poems have been vetted by independent editors. As a general observation, however, Australian presses have not insisted upon this practice with the same rigor as have their overseas counterparts, who frequently require that all (or nearly all) poems from a collection have first appeared in journals. It might well be in the interest of all to step up this practice. The so-called ‘big-eight’ of Australian literary journals – those that receive regular funding from the Literature Board – continue to publish a smattering of poetry and (usually bundled) reviews of poetry titles: Southerly, Meanjin, Overland, Quadrant, Island, Westerly, Hecate and Heat. Other journals of note include Westerly, Going Down Swinging, Tirra Lirra and Famous Reporter. Blast Magazine, Space: New Writing, Griffith Review and Wet Ink all began in the early part of the new century, while Salt-lick: New Writing disappeared soon after launching and Imago closed shop in 2001. Another birth worth noting was Ron Pretty’s revival of Poetry Australia, in this incarnation entitled Blue Dog: Australian Poetry, in 2003. Taking off in the late nineties, online poetry journals offer a new world of opportunity for editors not wanting (or unable) to finance expensive print journals. John Tranter’s Jacket, launched in 1997, was one of the earliest and has become the most eminent, bringing into conversation poets and critics from around the world. At reportedly over half-a-million hits since its inception, it is difficult to imagine a poetry journal in print format attracting a comparable amount of traffic. A short list of online poetry magazines that have steadily grown in profile might include Cordite, Stylus Poetry Journal, Divan, Retort, hutt and foame:e. There are also a number of online poetry resources, including the Australian Poetry Resources Internet Library project which presents poems and biographical information for Australian poets. In coming years the project plans to employ Digital Object Identifier (DOI) technology to allow poets the possibility of charging a reading fee to access copyrighted material. Eventually, the project will publish print-on-demand poetry books, particularly for titles that have gone out of print.[10]

These days a growing number of poets are not only using online technology to distribute and promote their work, they are also exploring digital media as an central part of the poetic experience. A small number of publications – including Les Murray’s Collected Poems (Duffy & Snellgrove, 2002) and literary journals Meanjin, Going Down Swinging and others – have experimented with audio CD attachments to books. Discarding the book entirely, the CD ROM journal papertiger: new world poetry published annually by Paul Hardacre, Brett Dionysius and Marissa Newell is one of Australia’s chief forums for digital poems. Not only does it publish poems that employ conventional textual layouts, it also incorporates to great effect audio, flash and video poems. Especially popular with younger audiences, the trend is likely to continue to develop new territories that reach new audiences. But it is not by any means unidirectional: the Newcastle Poetry Prize issued its 2003 anthology on CD ROM but reverted to print the following year; and papertiger media expanded its operations in 2006 to add print to its CD ROM and Internet formats, suggesting that the poetry book, while somewhat harder to find, has not entirely disappeared from fashion.

Notes

[1] See Pam Brown, ‘Nobody Wants Our Poems…’. The Sydney Morning Herald 26 February 2000 Spectrum: 10.

[2] See Christopher Pollnitz’s ‘Australian Verse Novels’, Heat 7 NS, 2004: 229-52.

[3] David McCooey, ‘Surviving Australian Poetry: The New Lyricism’. Agenda 41.1-2, 2005: 22.

[4] The Collected Verse of Mary Gilmore: Volume 2 edited by Jennifer Strauss is scheduled for release by UQP in July 2007.

[5] PAF also publishes the annual PAF Poetry Catalogue. The 2006 issue lists the 94 poetry titles by 20 Australian presses.

[6] Regional publishers of poetry include Fremantle Arts Centre Press in Western Australia; Spinifex Press in Victoria; Interactive Press in Queensland; Walleah Press in Tasmania; Ginninderra’s Indigo imprint in Canberra. Little Esther Books: Feral, Boffin + Distingué in South Australia focuses on avant garde poetry.

[7] See David McCooey, ‘Surviving Australian Poetry: The New Lyricism’. Agenda 41.1-2, 2005: 22-36.

[8] Sales figures for poetry books are notoriously difficult to verfiy. BookTrack keeps a record of sales but as most bookshops do not stock poetry books (most poetry books are sold at poetry readings and festivals and through online outlets) the figures are effectively meaningless. The 2001 AC Nielsen National Survey of Reading, Buying and Borrowing Books for Pleasure avoids poetry altogether.

[9] See Les Murray’s ‘On Being Subject Matter’ in A Working Forest: Selected Prose, Potts Point: Duffy & Snellgrove, 1997 (30-44).

[10] A similar project, Classic Australian Works (another CAL initiative), already provides print-on-demand re-releases of classic Australian books, with Bruce Beaver’s Letters to Live Poets as its first poetry title. For a detailed discussion of poetry and POD technology, see David Prater’s ‘Poetry Publishing Today’ in New Markets for Printed Books: Emerging Markets for Books, from Creator to Consumer. Ed. Bill Cope and Dean Mason. Altona, Vic: Common Ground Publishing, 2002.

♦

This chapter was first published as ‘Poetry Publishing’ in Making Books: Studies in Contemporary Australian Publishing. Ed David Carter and Anne Galligan. St Lucia: UQP, 2007: 247–54.

It was the focus of Rosemary Neill’s ‘Pulping Our Poetry’. The Weekend Australian 7–8 July 2007, Review: 4–5.

While Kevin Rudd was in Darwin proclaiming the need for “a national imagination” to grasp the economic potential of northern Australia, his Arts Minister, Tony Burke, was in Brisbane to celebrate the nation’s top imagination-makers at the Prime Minister’s Literary Awards, announced on the terrace of the State Library last night.

While Kevin Rudd was in Darwin proclaiming the need for “a national imagination” to grasp the economic potential of northern Australia, his Arts Minister, Tony Burke, was in Brisbane to celebrate the nation’s top imagination-makers at the Prime Minister’s Literary Awards, announced on the terrace of the State Library last night.![]()